May 25, 1924: The crossword hater

The New York Herald Tribune gave the crossword ample press in the early months of the craze, including coverage before and after the convention on May 18th. But not everyone writing for the Herald Tribune was on board.

Published in the May 25th edition, Dorothy Homans’ humorous essay “Diana of the Cross-Words” laments how the author’s life has been ruined ever since a friend, Diana, took up crossword solving.

I have always liked to talk to Diana, even when she went about saying ‘every day in every way I’m getting better and better.’ My friendship sustained her babbling about green dragons, east winds and heavenly twins. Now– well, I am afraid we have come to a parting at the cross-words. I am not strong enough (being already weakened by past experiences) to hear about ‘a minced form of the word God,’ ‘divine cedar,’ ‘Siamese coin’ and ‘barrage of the Nile.’

Homans goes on to describe occasions – a beautiful spring day, tea at the club – which Diana ruins by pressing her for answers.

Tea at the club is no longer what it used to be. I liked tea once. You drifted in thinking of nothing in particular. You stirred your tea slowly. You gazed out at the elms in Stuyvesant Square. But that was all before Diana and her friends took to cross-word puzzles.

Unlike Diana, Homans professes to have no interest in crosswords, describing them as “a combination of cross addition, the Einstein theory, and Roget’s ‘Thesaurus.’” She also speculates that their popularity is due to the end of the war, and muses that the puzzles might be a gateway drug to rediscovering other frivolous hobbies, like charades:

Nobody seems to have been curious as to why people are so interested in cross-word puzzles, aside from the fact that the year’s at spring. I blame it on the war. The younger generation at that time was so busy selling Liberty bonds, watching parades and taking part in peace pageants that they had not the time for the leisurely perusal of “St. Nicholas,” such as their parents had when they were young.

But before I continue I wish to warn Diana of charades. It’s been a long time since people wrapped themselves in couch covers and portiers and tried to act. It’s been so long that now some one could easily discover charades again. They are the next step.

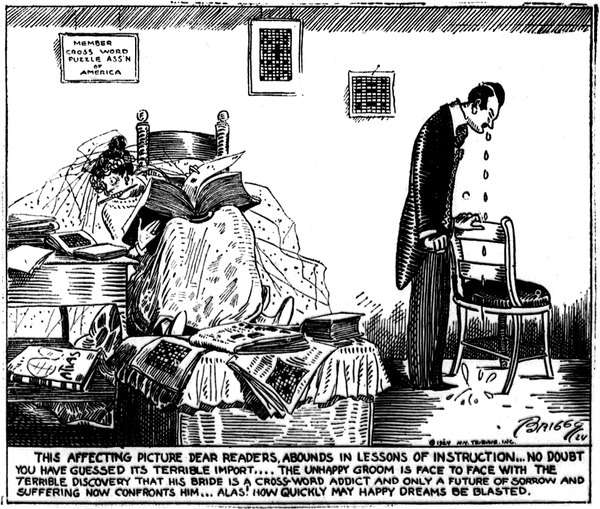

Crosswords infect every part of Diana’s life: they cause her to stay up late Saturday nights, in order to purchase the paper first thing Sunday morning; they leave her and her beau, Tommy Brent, no time for “petting”; they even make her stare at waffles, unconsciously trying to solve them.

Homans’ resentment of the crossword seems to be more than a matter of personal preference. It is likely that Homans, who would go on to write poetry, cultural commentary and “slice-of-life” pieces for the New Yorker, resented the puzzle’s incursion into New York literary life, and her complaint is an ideological as well as a practical one:

Since the intelligentsia have taken up the game Diana decided she must have a literary bent. Especially as she won 25 cents from Tommy Brent in one game.

She sarcastically proposes that soon poems and novels might start to take on the form of crossword clues.

THE PROBLEM NOVEL

My 27-14-5-3-2 is pertaining to husband or marriage.

My 29-13-6-7 is herbs dressed with vinegar.

My 28-13-8-7 is triangular.

My 29-1-4 and 9 is a complete change.

The Herald Tribune would continue to play both sides of the crossword craze, publishing crosswords and sponsoring competitions even as their comic strips and columns mocked enthusiasts as irritating or insane. As for Dorothy Homans, it seems her resentment did not go away even as crosswords proved themselves to be more than a fad. In a 1935 letter to the editor in the Saturday Review, Homans argues against opening the Morgan Library to the public and bemoans the state of public libraries. She describes an interaction with a librarian in which she informs him that she “would rather be shot at sunrise than solve a cross-word puzzle,” and compares crossword solvers to homeless, shoeless “down-and-outers” and “communists with mops of hair like black moss.” (Crossword puzzle addicts, she admits, at least “don’t smell as badly.”) She concludes the letter rather horribly:

Open the Morgan Library and who will throng its halls, pushing the gentle scholars away, ruining the silence for readers to whom Shelley, Pope, and Ben Jonson are not dehumanized? The rag-tail and bob-tail. The rabble. The down-and-outers. The feeble-minded (found in all these groups) and the cross-word puzzle addicts. Three threads that when woven together form the pattern of the Depression. Interesting to a historian, perhaps, but not to a bibliophile longing for the gentle peace that is to be found only in woods and libraries.

Perhaps Dorothy could have taken a cue from her friend Diana and learned to embrace the crossword, which was, after all, not going anywhere.