April 19, 1924: A peculiar recommendation

On Apr. 19, 1924, readers of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle would have found in the bottom corner of page 5 an endorsement of the newly published Cross Word Puzzle Book, colorfully written and ending in a jarring non-sequitur.

If you have any desire to go mad in the quickest and most enjoyable way, purchase at once “The Cross Word Puzzle Book,” published by the Plaza Publishing Company, and edited by those three clever tricksters of the Sunday World, Prosper Buranelli, F. Gregory Hartswick and Margaret Petherbridge.

He or she who has not known the hideous joy of figuring out “truncated,” in three letters, or “cigarette (British slang)” also in three, or some such annoying combination of vowels and consonants, has missed much. Here are fifty of the beastly things, selected with an uncanny shrewdness. Buy the book and beat your wife.

The author of the column, John Van Alstyne Weaver, had gotten married himself barely two months earlier, to actress Peggy Wood, best known to audiences today as the Reverend Mother in The Sound of Music.

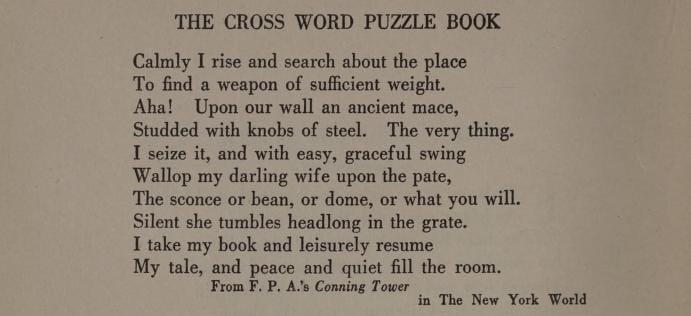

It is more than likely that “buy the book and beat your wife” is (what else?) a play on words: beat your wife at solving crosswords, or in acquiring the book first. But Weaver’s recommendation echoes the humor to be found in the book itself. The Cross Word Puzzle Book has as its epigraph a poem by Newman Levy, a lawyer and member of New York’s literary set who moonlighted as a poet. Levy was a friend of Franklin P. Adams, and FPA first published the poem in his New York World column “The Conning Tower” in June 1923.

FOR many years we’ve lived as man and wife,

As happy now as on the day we wed.

“We’re more like sweethearts,” I have always said.

No cloud has dimmed the sunshine of our life,

Though now and then I’ll seize a rolling pin

And playfully I’ll clout her on the dome

Just to preserve domestic discipline

And demonstrate who’s master in our home.

At times she’ll hurl with well-directed aim

A platter or an iron at my bean.

These slight attentions keep romances green

And keep alive the hymeneal flame.

On Sunday, when the evening lamp is lit

And peace and calm contentment fill our house,

With pipe and well-loved book at ease I sit,

And at my side, in earnest thought, my spouse,

Then fade the cares and troubles of the day;

With Conrad and Lord Jim I sail the sea,

When suddenly I hear my wife’s voice say,

“What word for ‘female child’ begins with G?”

“The world is ‘Girl’,” I growl. Again I try

To catch the shattered magic of my tale.

I find my place. Again with Jim I sail

Upon the tropic sea. My wife says “My,

What pronoun in three letters starts with Y?”

Calmly I rise and search about the place

To find a weapon of sufficient weight.

Aha! Upon our wall an ancient mace,

Studded with knobs of steel. The very thing.

I seize it, and with easy, graceful swing

Wallop my darling wife upon the pate,

The sconce or bean, or dome, or what you will.

Silent she tumbles headlong in the grate.

I take my book and leisurely resume

My tale, and peace and quiet fill the room.

It is hard to know what to make of these references taken together. One cheeky reference to domestic violence might be an anomaly; two start to form a pattern. Was wife-beating (and husband-beating) merely a common subject of humor in poems and columns of the time? Signs point to yes. Here is FPA himself, in a poem celebrating Freudian slips:

In the universal battle,

In the seraglio of life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle—

Beat your husband—or your wife.

And here is Gelett Burgess, later in 1924, in a crossword-themed take on his famous poem Goops:

The fans they lick their pencils,

The fans they beat their wives,

They look up words for extinct birds,

They lead such puzzling lives.

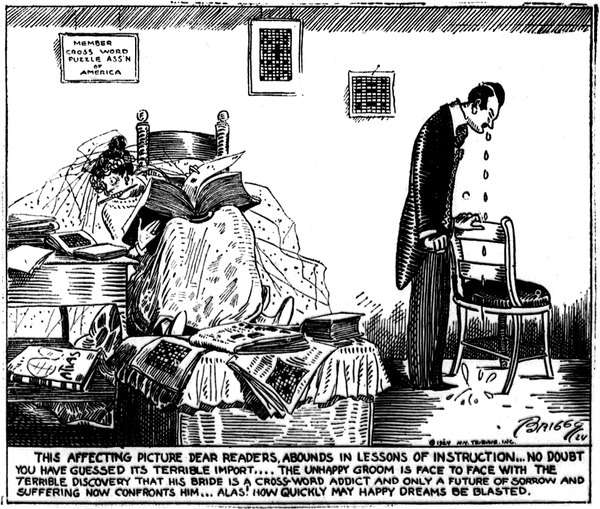

More than just an upsetting trend, the prevalence of domestic violence-based quips reveals the crossword’s emerging place in the domestic hearth. A Philadelphia Inquirer article from a year later, on Apr. 17, 1925, covers the results of a “cross-word contest,” and it largely centers around husbands, wives, and the relationship therein. Second-prize winner Mrs. E.J. Ryan is described to have worked on the puzzles “in spite of the handicap of two small and active children, who take up most of her time and energy.” Another entrant, Mrs. Elmer B. Carl, told the paper, “I must admit the end is rather opportune, for scores of little household duties are simply howling for attention.”

Mrs. Carl’s admission reflects a common fear in media coverage of the crossword craze: that puzzles were not only distracting women from motherhood and household tasks, but causing them to become obsessive or even licentious. The crossword, as Anna Shechtman writes in Riddles of the Sphinx, “became a locus for displaced anxiety about a movement that was explicitly challenging American gender relations: first wave feminism.” The preoccupation with domestic violence may have been evidence of the male observer’s desire to tame female crossword mania, or just a side effect of the puzzle’s association with domestic life.