Editor's Note: Guidelines for Aspiring Cruciverbalists

In February, 1914, Arthur Wynne—whose December 1913 “Word-Cross” birthed the American crossword as we know it—challenged solvers to transform themselves into contributors:

“FUN’s crossword puzzles apparently are getting more popular than ever. The puzzle editor has received from readers many interesting new cross-word puzzles, which he will be glad to use from time to time. It is more difficult to make up a crossword puzzle than it is to solve one. If you doubt this, try to make one yourself.”

Readers of the New York World were all too happy to oblige, and soon Wynne was overrun with submissions, many of which flouted some of the cruciverbal limitations today held dear: “Cross-word puzzles for FUN continue to arrive in all shapes in sizes.” As I write in my forthcoming book on crosswords, The Electric Grid, it was Margaret Farrar (then Petherbridge) who helped standardize what under Wynne was a chaotic process and product, when she was assigned to assist Wynne with the puzzle and later as his successor.

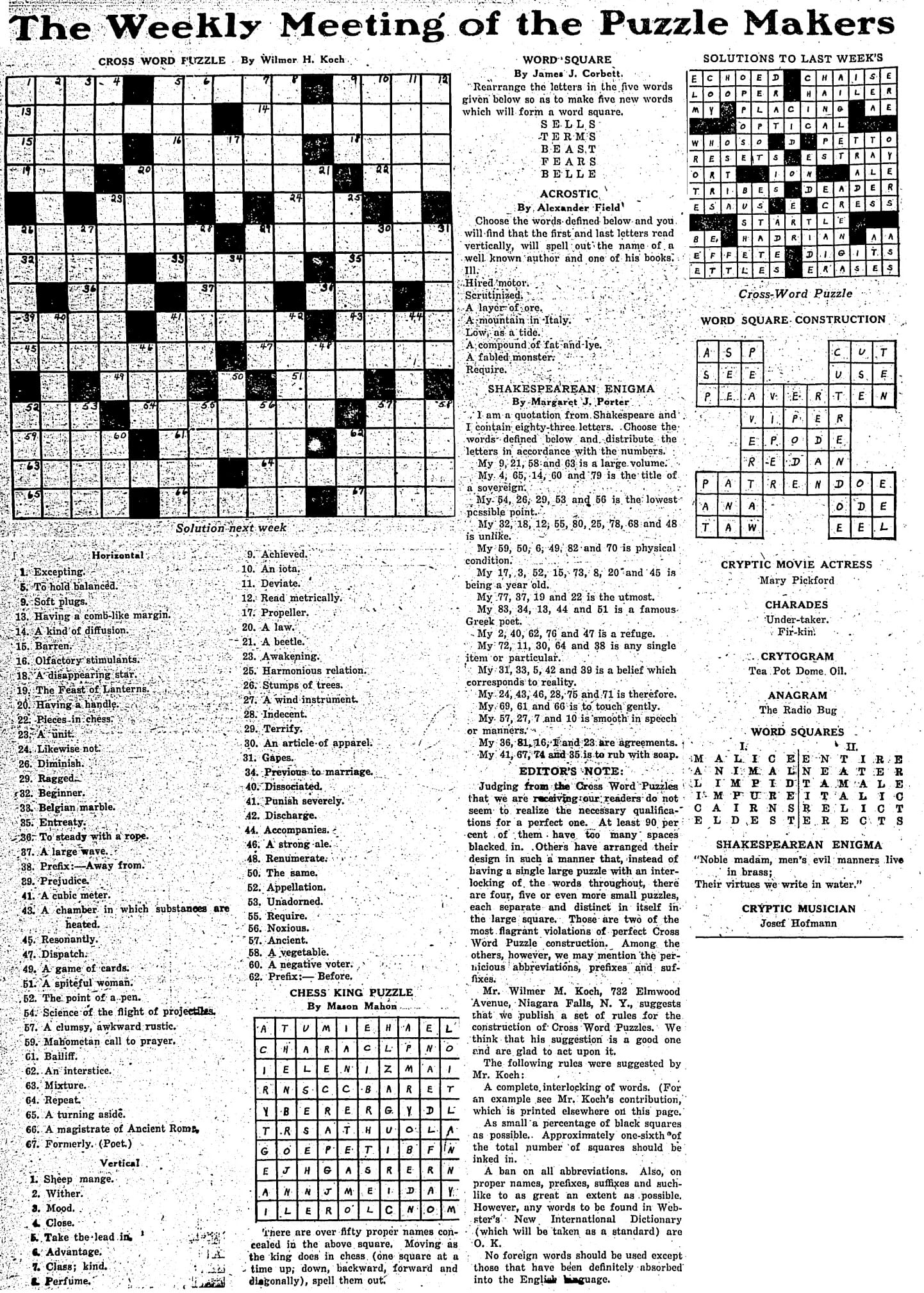

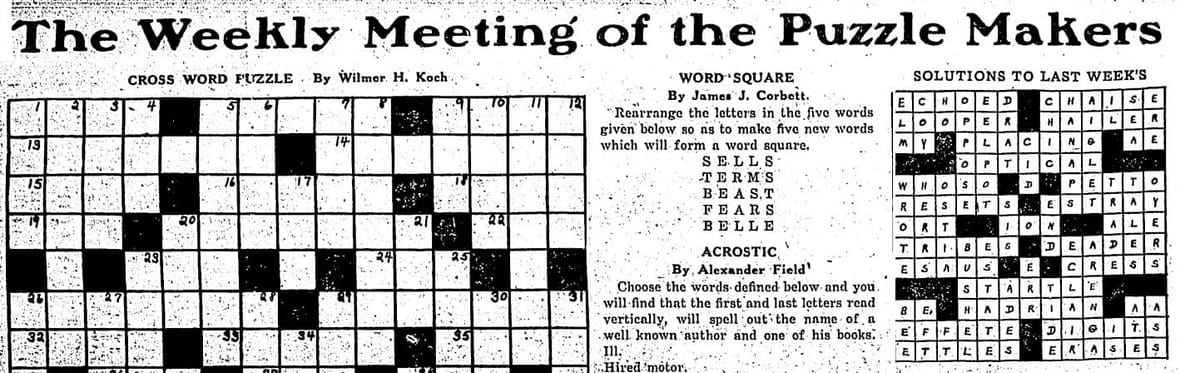

The editor’s note printed alongside the April 20, 1924 Herald-Tribune crossword shows that constructors and solvers themselves had a hand in shaping crossword standards. Here are Wilmer H. Koch’s suggested guidelines, quite similar to those adopted by the Amateur Cross Word Puzzle League of America a month later:

A complete interlocking of words. (For an example see Mr. Koch’s contribution, which is printed elsewhere on this page.)

As small a percentage of black squares as possible. Approximately one-sixth of the total number of squares should be inked in.

A ban on all abbreviations. Also, on proper names, prefixes, suffixes, and such-like to as great an extent as possible. However, any words to be found in Webster’s New International Dictionary (which will be taken as a standard) are O.K.

No foreign words should be used except those that have been definitely absorbed into the English language.

This last point, on foreign words and cross-linguistic absorption, is the subject of the first excerpt of my book, published recently in the New Yorker. A hundred years on, the question of what should or shouldn't be allowed in a crossword is no less hotly contested.

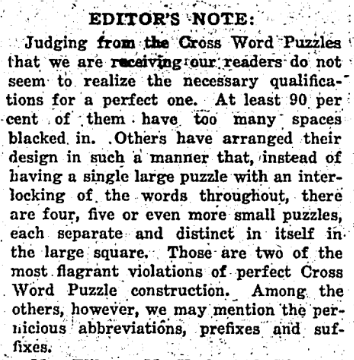

Judging from the Cross Word Puzzles that we are receiving our readers do not seem to realize the necessary qualifications for a perfect one. At least 90 per cent of them have too many spaces blacked in. Others have arranged their design in such a manner that, instead of having a single large puzzle with an interlocking of the words throughout, there are four, five or even more small puzzles, each separate and distinct in the large square. Those are two of the most flagrant violations of perfect Cross Word Puzzle construction. Among the others, however, we may mention the pernicious abbreviations, prefixes and suffixes.